Words to know: rhythm, notes, rests, beat, duration, measure, time signature

If this is your first time learning about music theory, you are in the right place! This post will show you everything you need to know to get started writing or understanding rhythms. If you already have a basic understanding of music, feel free to skip ahead to one of my other lessons.

The elements of music are rhythm, dynamics, form, melody, harmony, tempo, timbre, and texture, and are basically the building block of every song. Some of the elements go by different names in different parts of the world, but no matter what they’re called a piece of music can’t exist without them. Understanding how to use the elements together is the first step to being a great musician. Let’s get started!

What is Rhythm?

Because I am a trained percussionist, rhythm is one of my favorite elements of music. The simplest definition of rhythm is “the pattern of sounds and silence in music.” You may not have thought about it, but without sound there is no music (at least in the traditional sense), and without an occasional silence there would just be a wall of sound, which could be even more unpleasant. We need a good balance of sounds and silences to make a piece of music we enjoy listening to. In music, we call sounds “notes” and silences “rests.”

One thing that often gets confused with rhythm is the “beat” of a song. They are related, but not the same. The beat is the pulse of the music. Think about listening to a song you like. If you find yourself tapping your foot or bobbing your head along with the song, you are most likely moving to the beat. Rhythms are made up of beats.

Duration

An important part of rhythm is “duration,” or how long something lasts. Duration is not just a music word, but when we apply it to music we are specifically talking about how much time a note or a rest takes up. We label different notes and rests based on the number of beats they last. There are different names for different lengths of notes and rests, and they all relate back to the longest note we usually see: the whole note. Think of a whole note like a whole pie, and all of the other notes are just pieces of that pie. We use fraction names to talk about the other notes.

For example, a whole note has a duration of four beats. So, if we have a different note that is only two beats long, we would call that a half note, because two is half of four. If there was another note that was only one beat long, we would call that a quarter note, because one is 1/4th of four. We could go on dividing notes in half to eighth notes, sixteenth notes, thirty-second notes, and more, but the important thing to know is that they all get their names based on how many beats they last compared to a whole note.

Rests work the same way, and even have the same fraction names. For example, instead of “half note” for a rest, we would say “half rest”. A half note and a half rest are both worth two beats, but a half note is worth two beats of sound whereas a half rest is worth two beats of silence. Below is a chart with all of the note durations from whole notes to 16th notes, as well as what their pictures look like when we see them written in music.

| Note Names | Picture (Notes) | Rest Names | Picture (Rests) | Duration (In Beats) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Note | 𝅝 | Whole Rest | 𝄻 | 4 Beats |

| Half Note | 𝅗𝅥 | Half Rest | 𝄼 | 2 Beats |

| Quarter Note | ♩ | Quarter Rest | 𝄽 | 1 Beat |

| Eighth Note | 𝅘𝅥𝅮 | Eighth Rest | 𝄾 | 1/2 Beat |

| Sixteenth Note | 𝅘𝅥𝅯 | Sixteenth Rest | 𝄿 | 1/4 Beat |

Obviously, a song would be pretty boring if every note and rest was the same length. To help with that, composers have developed two other ideas: the “measure” and the “time signature.”

Measures

A measure, in music, is a small chunk of the total song that is a certain number of beats long. It is a way to make an entire piece of music a little easier to see and understand. It’s similar to the way books are broken down into sentences, rather than the entire book being one long sentence.

Typically in western music a measure is four beats long. It can contain any number of notes or rests, as long as their durations all added together equal the correct number of beats. The number of beats in a measure is set by the time signature, which we’ll talk about in the next section. You can add any number of measures to make a piece of music longer.

Think of a measure like a box. All boxes only have a certain amount of space before they get too full and you need another box. In music, the space in our box is often limited to four beats. So we could have four quarter notes in one measure, or we could have one whole note. We could have four eighth notes plus a quarter rest and a quarter note, or we could have two half rests. Any combination will work as long as we have the right number of beats. Below are some examples of measures with four beats of music.

*Note: usually, eighth notes and sixteenth notes are connected if there are more than one in a row, which makes them easier to read. The notes below connected with one bar are eighth notes, and the notes connected with two bars are sixteenth notes.

Time Signatures

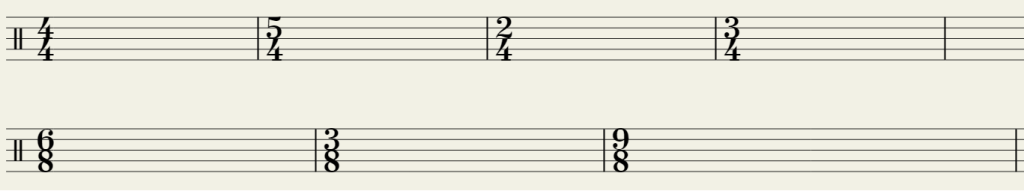

A time signature looks like a fraction and consists of two numbers: the top number tells you how many beats are in a measure, and the bottom number tells you what kind of note the measure is divided into. The most common time signature is 4/4, which means that there are four beats in the measure (as we mentioned earlier). However, time signatures can be very different from song to song or even measure-to-measure.

The top number of a time signature can be any number (though typically smaller numbers work better). For example, instead of a 4/4 measure you could have a 5/4 measure. In this case, the music would have 5 beats in a measure. The number of beats in the measure would be different but it would still be divided up into quarter notes. You could read this time signature as “5 quarter notes in a measure.”

The bottom number of a time signature can use the fraction name of any kind of note. You could also see an example of a time signature with an 8 on the bottom, like 6/8. In this case, you would have 6 beats in the measure because of the top number, but the measure would be divided up into eighth notes rather than quarter notes. You could read this as “6 eighth notes in a measure.”

Below are some examples of different time signatures you might see in music.

*Note: time signatures can change any time the composer wants, but are usually the same through entire songs. If you have one time signature, it will stay the same unless a new one is used.

Recap

In this lesson we talked about rhythm, and how it is divided up into beats. We talked about beats being either a note or a rest, and the durations of those notes and rests. We also talked about time signatures, measures, and how all of this works together to form pieces of music. This was a basic overview and there are many more things to get into when looking at rhythm. I hope you will start to write your own music and experiment with rhythm!

When you feel comfortable with rhythm, go on to my next lesson on dynamics! There is a lot more to learn about music and I’m happy to be able to help.

If you got value from this lesson, consider sharing this site with your friends who are interested in music. Also, don’t forget to subscribe to my website so you get notified when new lessons come out!

Thanks for reading, and have fun making music!